Mechanical Tension as a Stimulus in Energy Deficit

How load application generates adaptive signals independent of energy status.

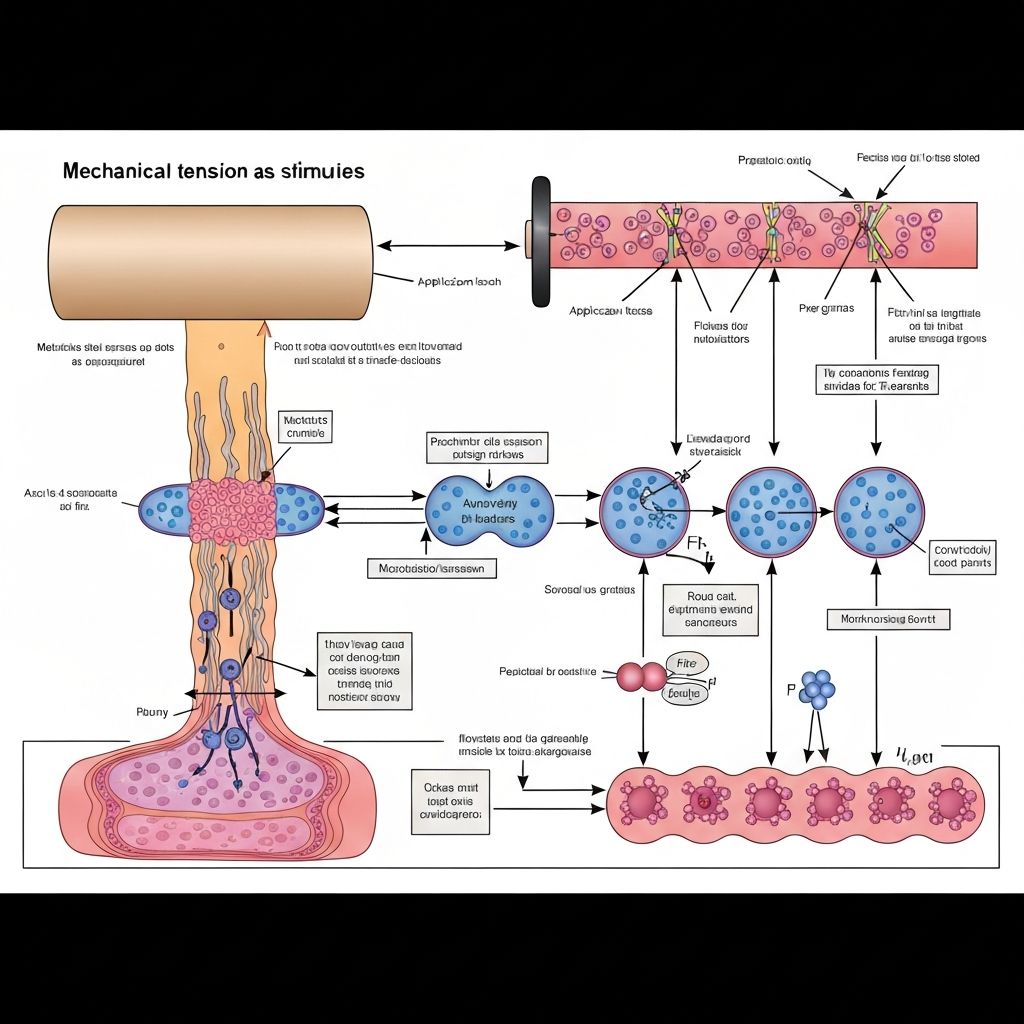

Tension: The Primary Stimulus for Adaptation

Mechanical tension is widely recognised as the primary stimulus driving muscle adaptation to resistance training. When external load is applied to muscle, the contractile apparatus (actin and myosin filaments) experiences direct deformation. Structural proteins including titins, nebulin, and dystrophin sense this mechanical change and activate signalling cascades within the muscle fibre.

The magnitude of tension is proportional to both load and muscle cross-sectional area. A given percentage of maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) generates consistent tension regardless of the total weight lifted. This principle is crucial to understanding why resistance training remains effective during energy deficit: the tension stimulus depends on the resistance used relative to capacity, not on systemic energy status.

Tension-Dependent mTOR Activation

Mechanical tension activates mTOR through several converging pathways. The primary mechanism involves calcium influx. Muscle contraction activates voltage-sensing mechanisms and releases calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Elevated intracellular calcium activates calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV (CaMKIV) and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases (CAMKs).

These kinases phosphorylate and inactivate TSC2, the negative regulator of mTOR. Inactivation of TSC2 permits mTOR activation independent of AMPK suppression or insulin signalling status. This mechanotransduction creates a pathway through which mechanical stimulus directly activates protein synthesis signalling despite energy deficit conditions.

Rho GTPase Signalling and Mechanotransduction

A second tension-dependent pathway involves Rho GTPases, particularly RhoA and Rac1. Mechanical stress activates guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that promote Rho GTPase activation. RhoA activates the formin mDia2, which triggers signalling cascades including activation of serum response factor (SRF) and downstream gene expression changes.

Additionally, RhoA-mediated actin dynamics directly affect mTOR localisation and activity. The mechanical deformation of cellular structures and the actin cytoskeleton appears to generate signals that enhance mTOR complex association with active signalling sites on the lysosomal membrane, the primary cellular location of mTOR activity.

Direct Mechanosensing by mTOR Complexes

Beyond secondary signalling through kinases and GTPases, emerging evidence suggests that mTOR complexes themselves possess mechanosensitive properties. The physical structure of the cell, particularly lysosomal positioning and the lipid composition of cellular membranes, responds to mechanical deformation. This altered cellular geometry may directly enhance mTOR complex activity by modifying the accessibility of mTOR to its substrates or by affecting the recruitment of regulatory proteins.

This hypothesis explains why acute resistance training generates strong mTOR activation signals independent of the energetic cost of the exercise. The mechanical stimulus itself, rather than any metabolic consequence of the training, appears to be the primary driver of activation.

Training Variables and Tension Magnitude

The degree of tension generated depends on the relative load, repetition scheme, and movement speed. Higher loads at lower repetitions (1–6 reps at 85–95% 1RM) generate peak tension but for brief durations. Moderate loads at higher repetitions (8–15 reps at 65–75% 1RM) generate lower peak tension but for extended durations. Very high repetitions (15+ reps) with lighter loads generate less peak tension and reduced overall tension accumulation.

Research suggests that peak tension magnitude matters most for maximising mTOR activation, but sustained tension duration also contributes. Resistance schemes emphasising moderate to high loads (65–85% 1RM) with controlled movement speeds appear optimal for tension stimulus. Importantly, this tension stimulus remains effective regardless of energy status—the resistance load needed to generate adaptive tension does not increase during energy deficit.

Tension and Protein Synthesis Response

Studies measuring acute muscle protein synthesis rates following resistance training consistently show that high-tension protocols elevate MPS for 24–48 hours post-exercise, even in energy-deficit conditions. The magnitude of this elevation is load-dependent: higher tension generates greater MPS stimulation than lower tension schemes.

This relationship provides a mechanistic explanation for why training with adequate load is more protective against lean mass loss during deficit than training with minimal load. The tension stimulus directly activates the mTOR pathway, creating a window of elevated protein synthesis that can shift net protein balance toward retention despite systemic energy limitation.

Implications for Training During Deficit

Understanding tension as the primary stimulus suggests that resistance training retains its effectiveness during energy deficit if adequate load is maintained. Progressive overload—gradually increasing the resistance or volume of training—may become more challenging during severe deficits due to reduced recovery capacity and neuromuscular fatigue, but the mechanism driving adaptation (mechanical tension) remains functional.

The practical implication is that maintaining high-tension training (moderate to heavy loads, 3–5 sets per exercise, controlled tempo) provides a better stimulus for muscle preservation during energy deficit than high-repetition, light-load protocols, despite the latter sometimes being recommended in popular fitness literature. The tension stimulus, not repetition number or training duration, determines the magnitude of protein synthesis stimulation and muscle preservation during energy restriction.

Important Limitations and Context

This article presents educational information on physiological mechanisms. Content is informational only and does not constitute personal exercise recommendations. Individual responses to training vary. For decisions regarding training practices, consult qualified professionals.